Why try a new language?

EDIT (11 Jan, 2023): I have been using Gleam for about 4 months now and I have written a couple of packages and other stuff, I have come to realise that a lot of the examples I gave here could have been done much cleaner, don’t let it discourage you from checking out the language.

I have been exploring a lot of languages recently, and I have stumbled upon the world of functional programming while doing that. Elixir was obviously my first go-to in that world but… I just couldn’t get it and I have no one to blame for that but myself (skill issue hehe). Let’s talk about why I am even exploring these languages to begin with (although there will be another article talking about my explorations and the languages themselves later). I primarily work in PHP, Go and Typescript, and I don’t think any of these languages are the best, but I enjoy using them, I know where and how they suck, I know where and how they shine, they get the job done and one of them even pays my tuition.

I started exploring other languages months back to see what I was missing out on, how my current languages could be better, find new ways to think about the same problem in these sometimes wildly different languages, just to have fun and to potentially add one more language to my stack for realtime applications (now you know how I landed on Elixir in the first place - Go and TS could already do real-time stuff to some extent, I mean almost every language can spin up a websocket, but it’s more than that, I am talking about a language/runtime designed and built to operate in that space and that’s Erlang/Erlang’s runtime). I’d love to go on and explain more on why I am exploring these languages but that’s not the point of this article, so let’s get to it.

What the heck is Gleam?

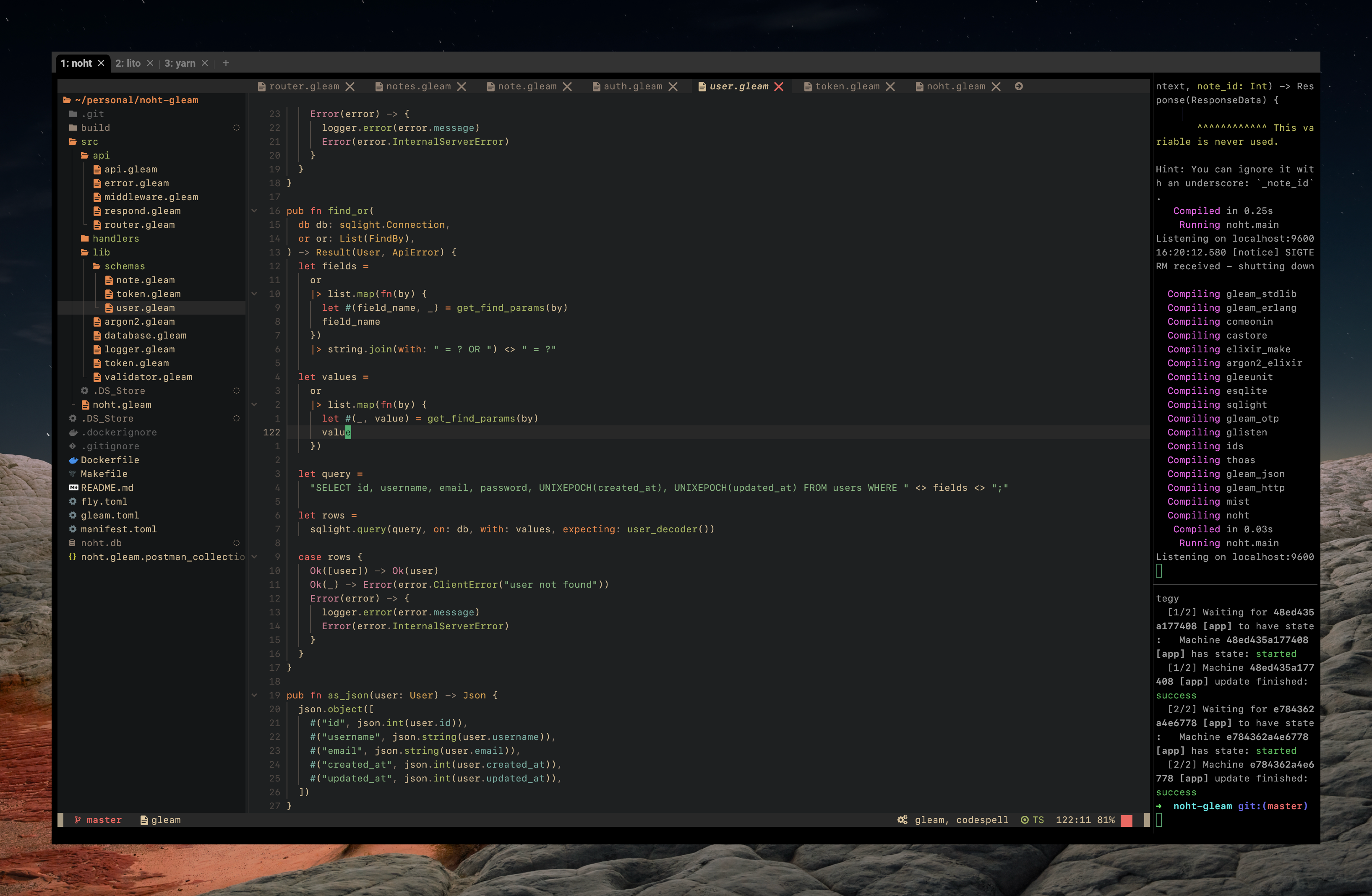

First time I ran into Gleam a couple of months back, I had the same question on my mind except I didn’t bother to try to get an answer at the time because it looked new and there was no way I was going to go on to build any of my real projects in that, plus Elixir was way more popular so of course it made more sense to learn that instead. Fast forwards to two weeks ago, I ran into Gleam again and this time I decided to at least read the docs and a few minutes in, I was in love with this language, I did not care that it was new, I knew I wanted to be in that ecosystem, so I created a new project and started building the same thing I build in any language I intend to use for web stuff; a notes API with auth (sort of, sign in and sign up). Okay, I actually haven’t given you a useful answer to the question yet, so let’s get to it. From their homepage:

Gleam is a friendly language for building type-safe systems that scale! The power of a type system, the expressiveness of functional programming, and the reliability of the highly concurrent, fault-tolerant Erlang runtime, with a familiar and modern syntax.

That is probably a lot to take in at once and you could say a lot of those things about Typescript too so, let’s talk about what makes Gleam, well, Gleam. For starters, it runs on the Erlang virtual machine (BEAM) which is known to be very fault-tolerant (also the same reason Elixir is so reliable, these languages are designed to handle crashing the best way possible; without affecting anything else running at the time), it also has a very familiar syntax if you have used Rust before, in fact, the compiler is built in Rust, and it borrows a lot of Rust’s syntax and constructs even down to the Option and Result types. Gleam is also a functional language, so you get all the goodies that come with that, like pattern matching, immutability, etc and unlike Elixir (Elixir is researching a type system at the time of writing this article), it is statically typed which means you can catch a lot of errors before and during compilation and just like the Rust compiler, the Gleam compiler guides you a lot in fixing these errors. I think that’s enough to get you started, let’s get to the fun part.

A note on immutability

While you can’t mutate variables or actual data in Gleam, you can rebind them, so you can do something like this:

let x = 1

let x = x + 1

// and of course, there are also constants

const y = 1

const y = y + 1 // this will not compile

I should also mention I am on the fence about immutability, it creates more memory and in turn more garbage, I don’t know if Gleam does something to keep that memory usage down, but it also makes it easier to reason about your code and makes it impossible to run into bugs that could be caused by mutation, so I don’t hate it but I don’t love it either.

The weird parts

Gleam being a functional programming language already makes it feel weird enough (although in my opinion, less weird than Elixir or Erlang itself, thanks to its Rust-like syntax) if you’re coming from other non-functional languages, but there are some other things that are just weird in Gleam, and I am going to talk about them here.

If statements, returns and loops

First thing to discuss here are if statements, return statements and for/while loops… or the lack thereof. Gleam does not have any of these constructs, instead, it leans heavily into pattern matching and recursion (although unlike Elixir, you cannot overload functions which makes it a bit trickier too) and I have mixed feelings about this decision, at first you wonder how you’ll do certain things but in reality, it doesn’t take away your ability to do the things you would normally have to do with these constructs, you just have to do them a bit differently and I appreciate the new thought process that comes with that but it also makes it extremely easy to nest match statements and that can get out of hand really quickly. As an example, say I need to validate some fields only when they are present in the request body, I would have to do something like this:

// decode the request body into a struct (sort of)

use body <- api.to_json( ctx,

dynamic.decode3(

UpdateNoteBody,

dynamic.field("title", dynamic.optional(dynamic.string)),

dynamic.field("body", dynamic.optional(dynamic.string)),

dynamic.field("folder_id", dynamic.optional(dynamic.int)),

),

)

let validations =

[]

|> fn(v) {

case body.title {

Some(title) ->

list.append(v, [

validator.Field(name: "title", value: title, rules: [

validator.Required, validator.MinLength(1), validator.MaxLength(255)

])

])

None -> v

}

}

|> fn(v) {

case body.body {

Some(body) ->

list.append(v, [

validator.Field(name: "body", value: body, rules: [validator.MaxLength(65_535)]),

])

None -> v

}

}

use <- api.validate_body(validations)

In this piece of code, we’re taking the raw JSON string into a Gleam type that we can use in our code, the use keyword in Gleam is a way to avoid nesting in some cases, it is also a bit weird at first but you can have a look at this to understand what it does. Unfortunately, in a lot of cases like this, you would need to use the use keyword and put things into new functions to avoid nesting and to do early returns, for example, in this example, the api.to_json method can only return an error response early if the request body doesn’t match what we need by either using a use statement like we have or going down the callback-like path which would end up being deeply nested. Although, I also think that the use keyword is a clever solution to the problem of early returns and nesting in Gleam (I mean, they did create the problem to begin with but it’s still clever).

The Gleam LSP

This one doesn’t really bother me much and it was sort of expected but I thought I should mention it still, the LSP is buggy sometimes, I don’t get definitions sometimes and other times I do, it doesn’t show the available methods in a module when I hit the dot (.) key, it goofs up with the types sometimes (shows the return type instead of the actual variable type) but all that being said, it is not a big deal. You’re probably thinking “What?? what the hell do you mean it’s not a big deal?” and I get you but really, it’s not and I’ll tell you why.

- When you screw up, the LSP and compiler will tell you (that one never failed for me), missing parameters and wrong types are also reported correctly - I am just saying all the things that are important to me are working fine.

- All packages, just like in Elixir, are automatically documented on Hex docs, even the standard library, so you can always go there to check what a function does and how to use it (although I wish the LSP would consistently show me the docs for a function when I hover over it, that would be nice).

- The language is stable enough considering how new it is, I can trust the compiler and seeing that only a few people work on it at the moment, I understand not having the best LSP in the world yet, I mean, it’s not like I am paying for it or anything, if I had to choose between a stable LSP and a stable compiler, I’d choose the compiler any day of the week.

- The cost of not having these things is negligible (to me of course), so I don’t really care that much.

Functions and modules

Recursion and function overloading is a very big part of Elixir, but in Gleam, you can’t have optional arguments that are just… not there, you can’t have different signatures for the same function (function overloading) in the same module, and don’t get me wrong, I am used to not having these things, it’s not a problem for me, it still has Option types for optional values and I personally don’t use any other language with support for function overloading either, but I am mentioning this because it’s a bit weird to see a language that is so similar to Elixir not have these things you’d expect it to have, it’s not a bad thing, it’s just weird. Also, Gleam uses files as modules which means everything related to a module has to live in the same file, Rust does similar thing to some extent, it’s up to you to decide if that’s a good thing or not, I personally don’t mind it.

So far, those are the only things I have found weird about Gleam, I am sure there are more but I haven’t run into them yet, I’ll update this article if I do.

EDIT (11 Jan, 2024): Due to the lack of any meta-programming features, Gleam requires you to write

decoders(see this example) for transforming data into type-safe Gleam structures. Writing decoders also became frustrating because the stdlib only comes with adecode9function as the maximum (which means you can only use the standard library’s convenient functions to write decoders for up to 9 fields, anything more and you have to painfully hand-roll it), but there are also talks in the community on how to solve this in the language itself in the future.

EDIT (11 Jan, 2024): I picked up Gleam to get the Erlang/BEAM benefits in a familiar body but since Gleam has to care about Javascript and eventually WASM, most of the native constructs that allow you to easily use those things (

receivemainly) or even write Erlang directly in a language like Elixir cannot simply be added to the language (the way Javascript works is very different to how the BEAM does stuff, especially when doing async work/the concurrency models as I understand it).

The good parts

Now that we have talked about the weird parts, let’s talk about the good parts, the parts that make me want to use Gleam everyday, and boy, there are a lot of them. I am not going to talk about the BEAM, OTP and all that stuff, I am going to focus on the language itself and I will try to keep it short.

The compiler and the guard rails

This is probably the best thing about Gleam, just like Rust, the compiler uses the information it has of the code it is running/building to help the programmer (I wish Go would take hints). The compiler is also pretty fast but to be honest, blazing fast speed isn’t why anyone uses any of these languages and that’s fine, although Gleam is still plenty fast. Like Go, and unlike Rust, Gleam does have Nil but unlike Go, it protects you from shooting yourself with it, in fact, every bug I have run into so far while building this tiny project has been my fault for not paying attention, really! There has been no case of the language letting me do things I shouldn’t be doing, like attempting to use an empty value as a non-empty one, thanks to the presence of the Option type, it forces you to do a check before you can use the value (although it has a let assert Ok(_) = ... sort of expression to blow things up if they don’t match what you want, I avoid that). Gleam also handles errors really well and I am not talking about the OTP this time, Gleam has a Result type that you can use to handle errors and it is very similar to Rust’s Result type, it makes sure you know what functions can fail and cause an error return an error, you can read more about it here.

The standard library, ecosystem and interop

Gleam has a small and rich ecosystem at the same time, rich in the sense that the standard library (which in itself is a package you can choose not to install) has a very large percent of what you’ll need to do what you need to and small in the sense that there are very few 3rd-party packages compared to more matured languages (expected and obvious) and that includes packages like json managed by the Gleam team which is somehow not in the stdlib (?) and you will have to reach into another language for those things.

I know, I know, you are thinking this language is so poor you have to reach into other languages to find packages you need to get work done (“What the…? Why would I want to do that??”), Gleam is a new language and I don’t expect it to have a butt-load of third-party packages available already (Zig doesn’t even have a package manager yet but it’s been used for large programs!), but this ability to reach into other languages is actually a strength of Gleam. Using the @external macro attribute (You can’t create custom macros attributes yet AFAIK), you can not only reach into Elixir, Erlang and LFE but you can also reach into Javascript. Yes, you read that right, Gleam can run with a Javascript runtime as the target and as if that wasn’t good enough, almost every Elixir and Erlang package is compatible with Gleam, so you can use them in your Gleam project, I mean, how cool is that? I am not going to talk about the interop with Javascript because I haven’t tried it yet but I am sure it’s just as good as the Elixir/Erlang interop (I used “almost” here because I have been told Gleam cannot handle Elixir macros for certain good reasons). Here is an example of using the Elixir argon2_elixir package in gleam for password hashing:

# install the package

gleam add argon2_elixir

And here is how you use it in your Gleam code:

// lib/argon2.gleam

@external(erlang, "Elixir.Argon2", "hash_pwd_salt")

pub fn hash_password(password: String) -> String

@external(erlang, "Elixir.Argon2", "verify_pass")

pub fn compare_password(password: String, hash: String) -> Bool

Using the package in your code is as simple as importing the module and calling the functions:

// handlers/auth.gleam

import lib/argon2

...

let hashed_password = argon2.hash_password(password)

...

This is extremely powerful and I am sure it will only get better with time, it also means you don’t just have the Gleam ecosystem, you have the Elixir/Erlang ecosystem too, and that’s a lot of packages that have been battle-tested for years, and you can even, in theory, use Javascript packages by using them in your custom Javascript code and then using that in your Gleam code, I haven’t tried it yet but it’s most likely possible.

EDIT (11 Jan, 2024): Gleam has no macros,

@external,@targetetc. are all attributes, this is by design; although there have been talks about some meta-programming capability in the future.

Pattern matching

This part isn’t Gleam-specific but until you try pattern matching, you have no idea how awesome it is! Pattern matching allows you to do a lot of cool stuff like using the language itself as your router like this:

pub fn router(ctx: Context) -> Response(ResponseData) {

case ctx.path {

["ping"] -> handle_ping(ctx)

["@me"] | ["me"] -> auth.me(ctx)

["auth", ..path] ->

case path {

["sign-up"] -> auth.sign_up(ctx)

["sign-in"] -> auth.sign_in(ctx)

}

["notes"] -> notes.handle_root(ctx)

["notes", id] -> notes.handle_id(ctx, id)

_ -> respond.with_err(err: error.NotFound, errors: [])

}

}

// handlers/notes.gleam

pub fn handle_root(ctx: Context) -> Response(ResponseData) {

case ctx.method {

Get -> get_all(ctx)

Post -> create(ctx)

_ ->

respond.with_err(

err: error.MethodNotAllowed(method: ctx.method, path: ctx.path),

errors: [],

)

}

}

pub fn handle_id(ctx: Context, note_id: String) -> Response(ResponseData) {

let id = int.parse(note_id)

case id {

Ok(id) ->

case ctx.method {

Get -> get_one(ctx, id)

Patch -> update(ctx, id)

Delete -> delete(ctx, id)

_ ->

respond.with_err(

err: error.MethodNotAllowed(method: ctx.method, path: ctx.path),

errors: [],

)

}

Error(_) ->

respond.with_err(

err: error.ClientError("Invalid note id, must be an integer"),

errors: [],

)

}

}

Pattern matching in Gleam (and a lot of other languages) makes sure you perform all the checks you need to perform and it also makes sure you don’t forget to handle all the cases you need to handle, it is also very easy to understand and use, I love it.

The Gleam community

This is the first time I have been in a Discord/Slack for a specific language so, these things are most definitely not specific to Gleam, but it has an awesome community of people constantly building things and willing to help you out, I have asked a few questions and I have gotten answers to all of them pretty fast, I have also seen a lot of people ask questions and get answers, it’s a very friendly community and I am glad to be a part of it, albeit a very small part.

Conclusion

I know I have really compressed the good parts but when you weigh both the good parts and the bad parts and/or you use Gleam for a while, you’ll realise that the good parts are really good and the bad parts are not that bad, in fact, they’re not even bad, they’re just weird and they will either get better as the language matures and/or you will get used to them. I am not saying Gleam is perfect, it is not, but it is a very good language and I am sure it will only get better with time, I am definitely going to be using it for a while and I am sure I’ll be writing more about it in the future.

If you want to learn more about Gleam, you can check out the official docs and the language tour, they’re both very good and will get you started in no time. If you are interested in the project I have been building with Gleam, you can check it out here

I hope you enjoyed reading this article, I’ll see you in the next one, you can always give me a shout on Twitter if you have any questions, suggestions, corrections or just want to say hi :)

I am not a Gleam expert by any means, I have only been using it for about two weeks now so, many of the code examples here might not be the best way to do things, I am still learning and I am sure I’ll get better with time, so please, if you see anything that can be improved, let me know, I’ll be happy to learn from you.